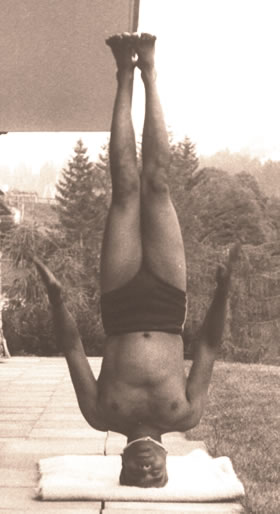

Anybody who has been to one of my classes, seen me at the

beach, looked at my Facebook profile or indeed met me, will likely know that I

REALLY like to stand on my head.

Why should we stand

upon our think-boxes?

There are so many benefits of sirsasana (sirsa = head, asana = posture); google the word and

a plethora of articles detailing the benefits will pop up. Most will list

physical benefits such as increased core and shoulder strength, improved blood

circulation, stimulation of the pineal gland, and alleviation of ailments such

as constipation, low blood pressure, colds, anxiety symptoms, depression and

frequent headaches. Some also mention increased sexual energy, which is likely

linked to the stimulation of the pineal gland, and a handful make references to

reported “yogasms” (yoga-induced orgasms) through sirsasana practice. If nothing

else persuades you to turn your world upside-down, I hope that does.

Personally, I just love being upside-down. I find headstands

energizing, exhilarating, and that they significantly reduce feelings of

anxiety.

Conflicting headstand

advice

If you try different types of yoga (or come from a different

background such as gymnastics), you will likely encounter lots of conflicting

advice on practicing headstand, and it can be pretty confusing. As a fairly

competent head-stander, I was shocked and rather indignant to go to an Ashtanga

teacher training school and find that I was doing it “wrong”. I’ve since done some reading, lots of practice

and a fair bit of upside-down thinking in order to summarize the differences

between different styles, and to discern which pieces of advice we should take

from the Ashtanga and Iyengar yoga systems.

Where is the weight?

Pattabhi Jois (founder of the Ashtanga system) says that the

head should only lightly touch the floor, and that carrying the body weight in

the head will impinge intellectual development.

Conversely, BKS Iyengar (founder of the Iyengar yoga system)

says “the whole weight of the body alone should be borne on the head alone and

not on the forearms or hands. The forearms and hands are to be used only for

support to check any loss of balance.” (Light

on Yoga p.149).

|

Iyengar's intellectual development does not appear to be impinged as he demonstrates that hands and forearms are not necessary for an impressive sirsasana

|

This is pretty contradictory advice, and this is just one

example of where Ashtanga differs from Iyengar in the teaching of sirsasana.

Personally, I believe that the headstand should ultimately be just that; the

weight should be in the head. I can’t promise it won’t impinge your intellectual

development, but it will definitely provide a better base for transitions

between headstand variations.

If the weight is in the head, the arms are free to change

positions, and we can go through the entire sirsasana cycle without exiting the

posture until the end. So, ultimately, I’m with Iyengar.

For beginners, however, I think that placing the weight in

the hands and forearms can reduce the discomfort in the head and cervical spine

that many people report. The Ashtanga way, therefore, might be useful for

beginners as they become accustomed to being upside-down. As disorientation

wears off (and it does!) and balance becomes easier, weight can be transferred

from the hands to the head. The Ashtanga way is also useful if you want to

transition from a headstand to a forearm stand without bringing the feet back

to the floor. That is probably the only thing I’ve really taken from my

Ashtanga-style sirsasana practice.

In summary, ultimately

aim for weight in the head, but make use of the hands and forearms as you build

up to this. Ashtanga weight placement is good for beginners, but Iyengar’s is

the one to strive for.

How to enter the

headstand

Ashtanga teachers will encourage beginners to enter the

headstand with both legs together. If this works for you, great. Carry on. If

it doesn’t, try another way.

Iyengar suggests that all beginners use the support of a friend or wall. Both can be very supportive, especially that sturdy wall with its tacit approval. Nobody likes a suck-up.

If you don’t want to rely on a wall or indeed a friend, I recommend entering the headstand one leg at a time. Walk the feet towards the head, and lift one leg as high as possible. Rock the weight into the head and gradually allow momentum to take the other leg off the floor. It might not happen first time, but this preparatory position will allow you to get used to the sensation of being inverted, of placing the weight in the head (and/or hands and forearms), and of engaging the core as you attempt bring the legs upwards.

|

| Brad hits tripod headstand at the first time of trying using the single leg method |

If your core strength is good, I also suggest trying to

enter headstand from straddle. I find this the easiest way to enter headstand,

and whilst I can’t speak for total beginners, I imagine it would be a nice

intermediary stage between bent legs or single leg entrances and entrances from

pike position.

|

| Entering from straddle uses less momentum and therefore more core strength; its a graceful and versatile entrance to the asana. Wear a proper top, though... |

In summary, try

both the Ashtanga and Iyengar ways of entering headstand, and if neither feels

right, try my way. It isn’t how I learned, but it’s the method I’ve had most

success in teaching. If you are comfortable entering headstand with bent legs

or one leg at a time but can’t yet manage to enter from pike (both legs rising

together and remaining straight), try from straddle.

Which variation is

easiest?

Again, Ashtanga is prescriptive in that it suggest beginning

with salamaba sirsasana (supported headstand) in which the hands clasp the back

of the head. I was told that tripod “doesn’t really do anything” when I entered

headstand in India. I disagree. I learned to stand on my head in

tripod, and became so comfortable with it that I developed the strength and

confidence to swap every other hand placement from there without exiting the

posture. Whilst I am capable of entering headstand from each recognized arm

position, it’s much more fun to flow through positions without exiting the

postures each time.

Yoga is very personal; what some people find easy, others

don’t. It is ludicrous to suggest that yoga follow a set progression of

postures becoming more and more advanced. I can happily hang out in any variation

of headstand all day, popping up to forearms and handstand variations as I

please. But can I squat all the way down with my heels on the floor? Absolutely

not. I love pigeon more than the old bird woman of the steps of St Paul’s in

Mary Poppins, but can I even come close to supta kurmasana? Nope. We all have

different skeletal structures, strengths, weaknesses, and preferences.

|

| Katy opts for a supported headstand preparation with weight in the forearms rather than tripod |

So my advice would be to place the head on the floor and

place the arms in WHICHEVER POSITION YOU FIND MOST COMFORTABLE. That’s right;

if forearms down feels too weird, just place the hands on the floor. If bound

arms (hands holding opposite elbows on the forehead side of the head) feels

right, do that. If you are able to take the weight in the head, play around with that.

In summary, do

whatever you want. Play about with headstand. Become comfortable and confident in

the posture. Indulge in the joys of being upside-down. Once you find your favourite

variation, you can begin to try others from that base. Your base might be

different to somebody else’s, and that’s ok.

And so, my fellow yogis, go forth and stand upon your heads. Engage your cores, stimulate your pineal glands, and, if you're lucky, have super intense orgasms.

Namaste :)

Emma

xxx